Abstract¶

This notebook provides a comprehensive introduction to data visualization in Python using Matplotlib and Pyplot. It covers the basics of creating visualizations such as histograms, scatterplots, and bar charts, while emphasizing their importance in exploratory data analysis, communicating insights, and making impactful decisions. Practical examples and best practices are included to help users effectively visualize and interpret data.

Chapters 5-6-7¶

In the following chapters we will delve into data visualization.

How to create visualizations in Python?

What principles should we remember?

How to work with Matplotlib, Pyplot?

How to work on visualizations in Seaborn?

What are the best practices for creating data visualizations?

Next, before we start statistical analysis, we will work on managing and cleaning our data.

How to deal with missing values?

How to deal with dirty data?

What are the basic ways to describe data?

Remember that these chapters are an integral part of Exploratory Data Analysis in Python.

In this chapter¶

What is data visualization and why is it important?

Introduction to

matplotlib.Types of one-dimensional charts:

Histograms (one-dimensional).

Scatterplots (two-dimensional).

Bar charts (also two-dimensional).

Introduction: data visualization¶

What is data visualization?¶

Data visualization refers to the process (and result) of representing data graphically.

For our purposes today, we’ll be talking mostly about common methods of plotting data, including:

Histograms

Scatterplots

Line plots

Bar plots

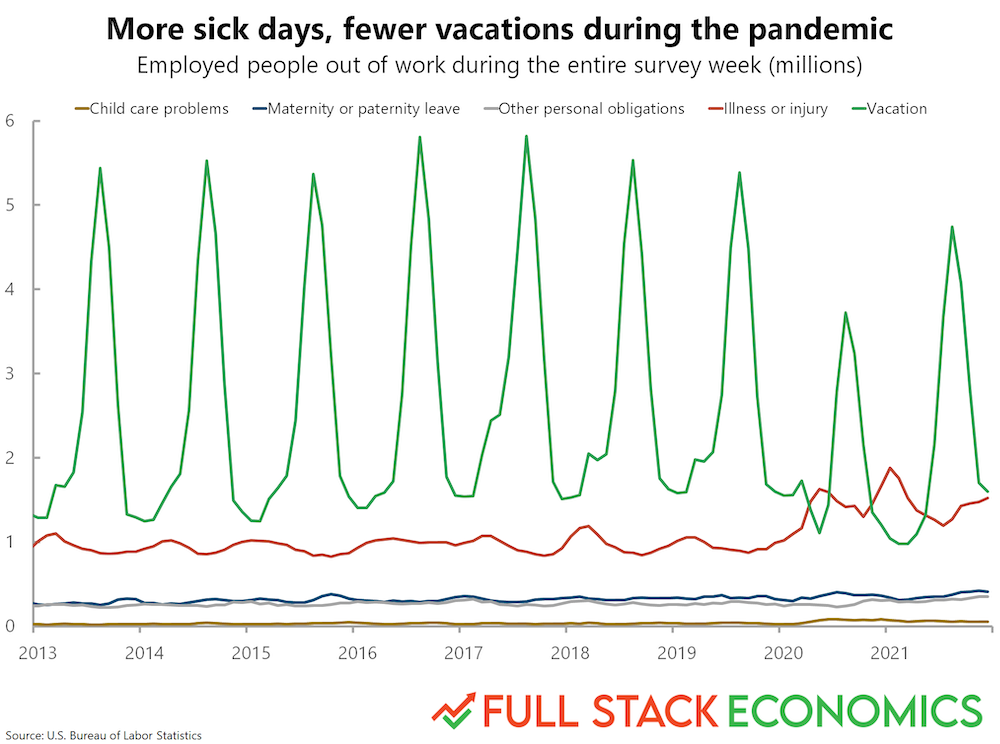

Why is data visualization important?¶

Exploratory data analysis

Communicating insights

Impacting the world

Impacting the world¶

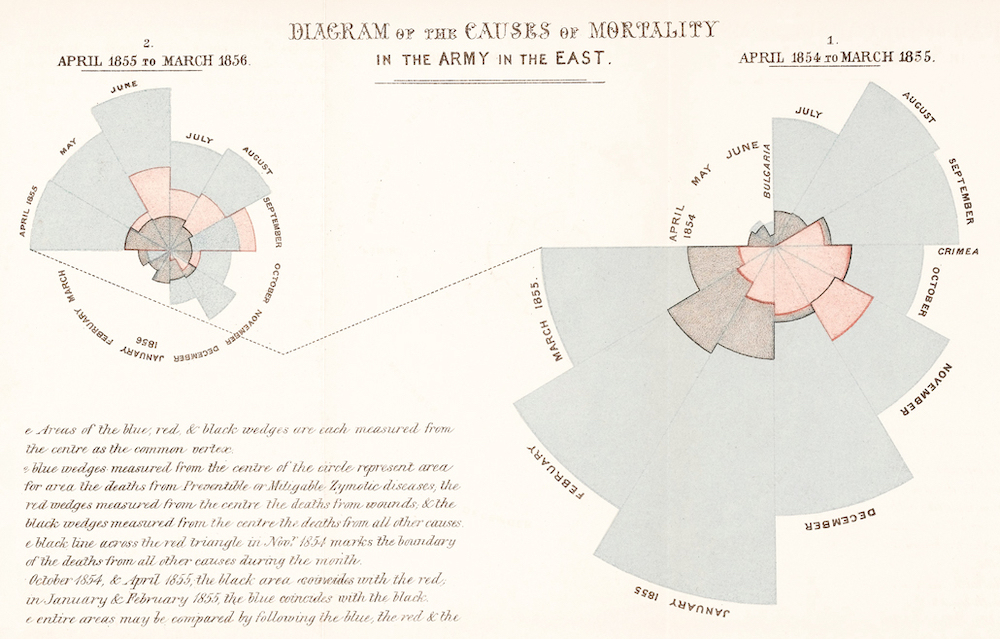

Florence Nightingale (1820-1910) was a social reformer, statistician, and founder of modern nursing.

Impacting the world (pt. 2)¶

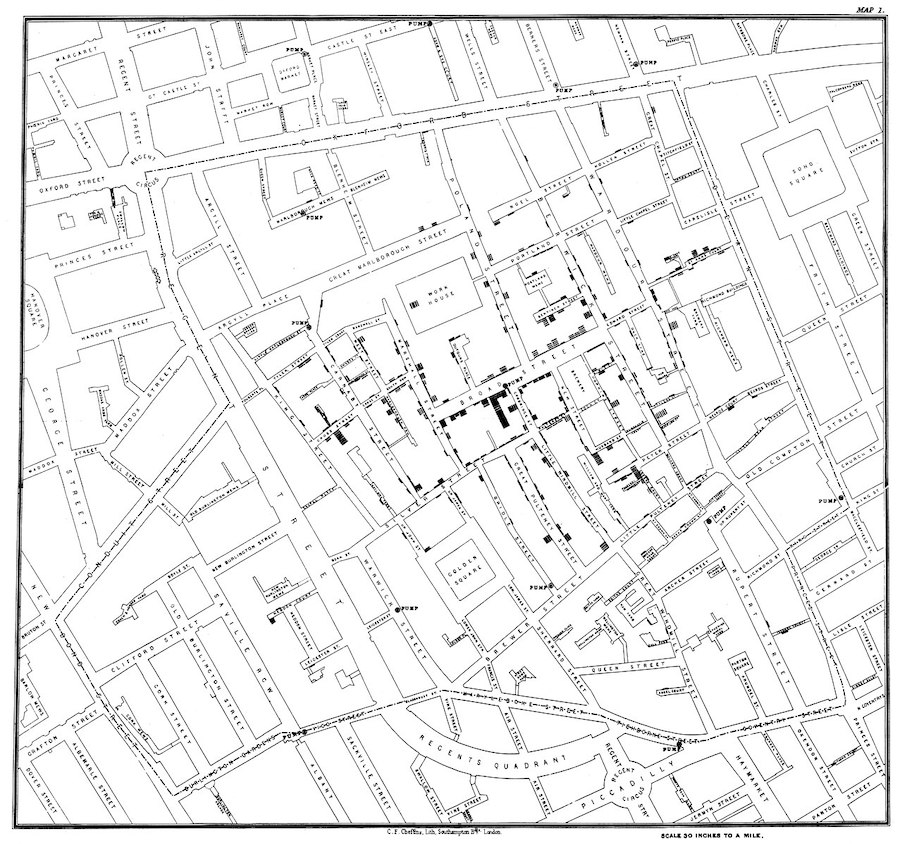

John Snow (1813-1858) was a physician whose visualization of cholera outbreaks helped identify the source and spreading mechanism (water supply).

Introducing matplotlib¶

Loading packages¶

Here, we load the core packages we’ll be using.

We also add some lines of code that make sure our visualizations will plot “inline” with our code, and that they’ll have nice, crisp quality.

import numpy as np

import pandas as pd

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import scipy.stats as ss/opt/anaconda3/lib/python3.9/site-packages/scipy/__init__.py:146: UserWarning: A NumPy version >=1.16.5 and <1.23.0 is required for this version of SciPy (detected version 1.23.1

warnings.warn(f"A NumPy version >={np_minversion} and <{np_maxversion}"

%matplotlib inline

%config InlineBackend.figure_format = 'retina'What is matplotlib?¶

matplotlibis a plotting library for Python.

Note that seaborn (which we’ll cover soon) uses matplotlib “under the hood”.

What is pyplot?¶

pyplotis a collection of functions withinmatplotlibthat make it really easy to plot data.

With pyplot, we can easily plot things like:

Histograms (

plt.hist)Scatterplots (

plt.scatter)Line plots (

plt.plot)Bar plots (

plt.bar)

Example dataset¶

Let’s load our familiar Pokemon dataset, which can be found in data/pokemon.csv.

df_pokemon = pd.read_csv("data/pokemon.csv")

df_pokemon.head(3)Histograms¶

What are histograms?¶

A histogram is a visualization of a single continuous, quantitative variable (e.g., income or temperature).

Histograms are useful for looking at how a variable distributes.

Can be used to determine whether a distribution is normal, skewed, or bimodal.

A histogram is a univariate plot, i.e., it displays only a single variable.

Histograms in matplotlib¶

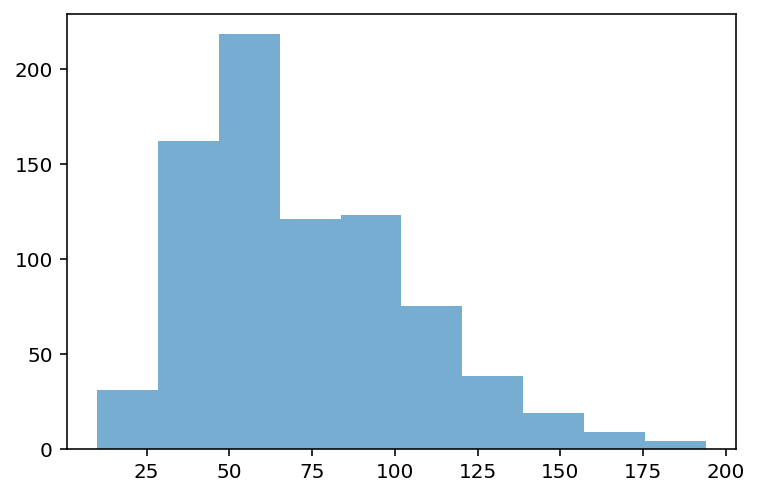

To create a histogram, call plt.hist with a single column of a DataFrame (or a numpy.ndarray).

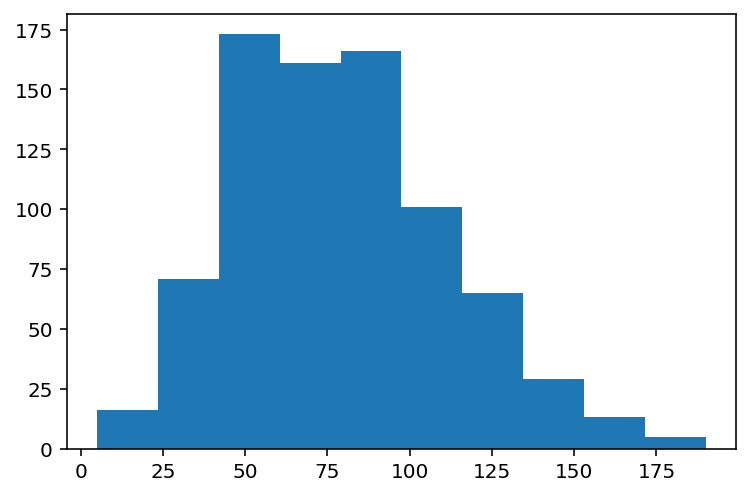

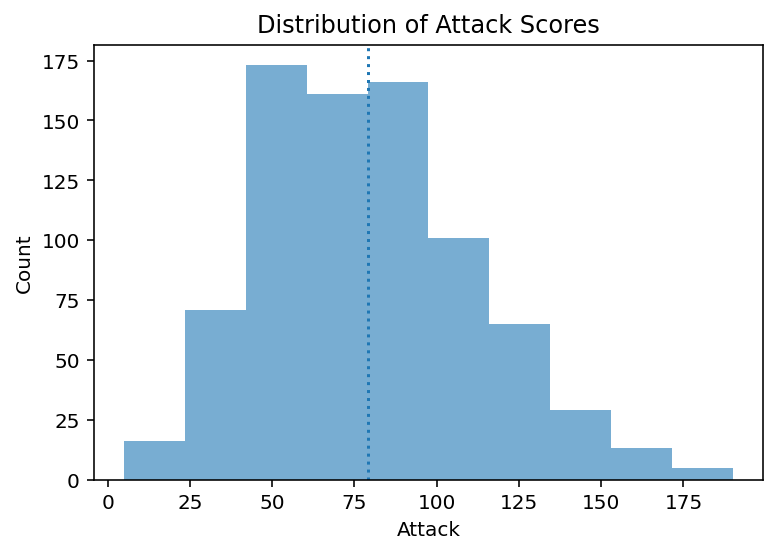

Check-in: What is this graph telling us?

p = plt.hist(df_pokemon['Attack'])

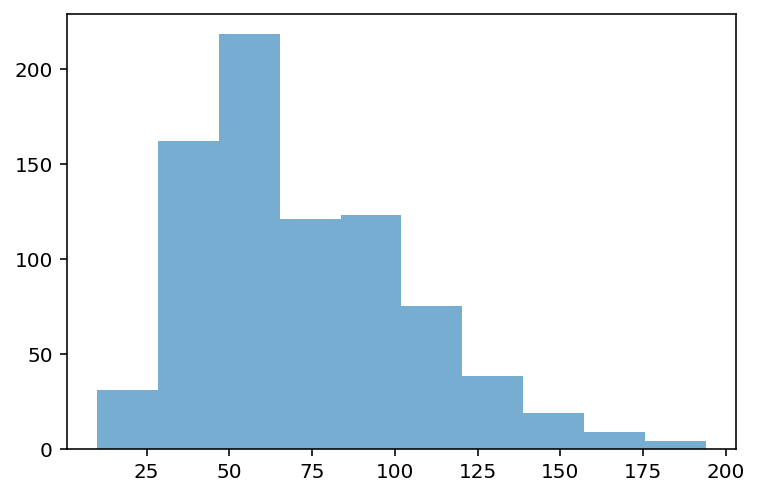

Changing the number of bins¶

A histogram puts your continuous data into bins (e.g., 1-10, 11-20, etc.).

The height of each bin reflects the number of observations within that interval.

Increasing or decreasing the number of bins gives you more or less granularity in your distribution.

### This has lots of bins

p = plt.hist(df_pokemon['Attack'], bins = 30)

### This has fewer bins

p = plt.hist(df_pokemon['Attack'], bins = 5)

Changing the alpha level¶

The alpha level changes the transparency of your figure.

### This has fewer bins

p = plt.hist(df_pokemon['Attack'], alpha = .6)

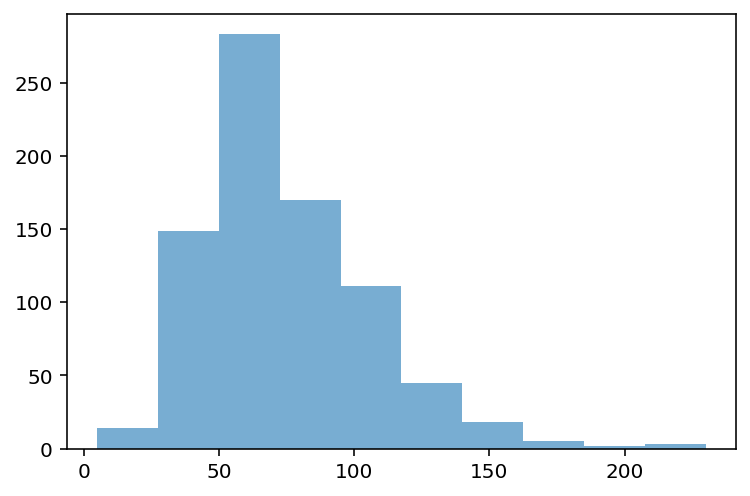

Check-in:¶

How would you make a histogram of the scores for Defense?

### Your code hereSolution¶

p = plt.hist(df_pokemon['Defense'], alpha = .6)

Check-in:¶

Could you make a histogram of the scores for Type 1?

### Your code hereSolution¶

Not exactly.

Type 1is a categorical variable, so there’s no intrinsic ordering.The closest we could do is count the number of each

Type 1and then plot those counts.

Learning from histograms¶

Histograms are incredibly useful for learning about the shape of our distribution. We can ask questions like:

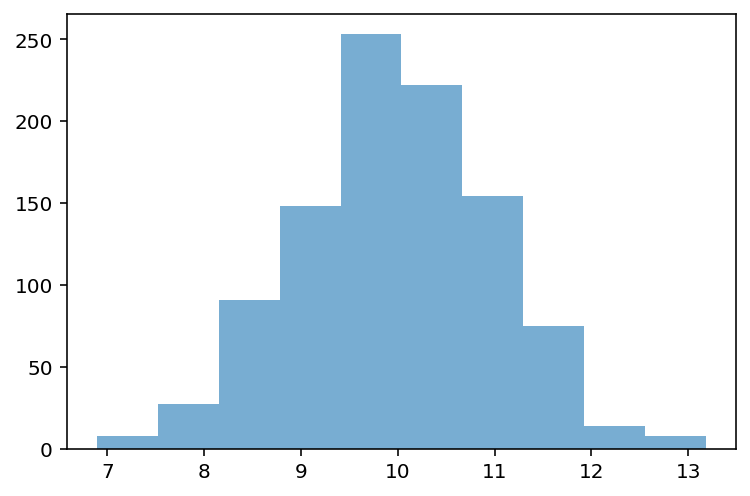

Normally distributed data¶

We can use the numpy.random.normal function to create a normal distribution, then plot it.

A normal distribution has the following characteristics:

Classic “bell” shape (symmetric).

Mean, median, and mode are all identical.

norm = np.random.normal(loc = 10, scale = 1, size = 1000)

p = plt.hist(norm, alpha = .6)

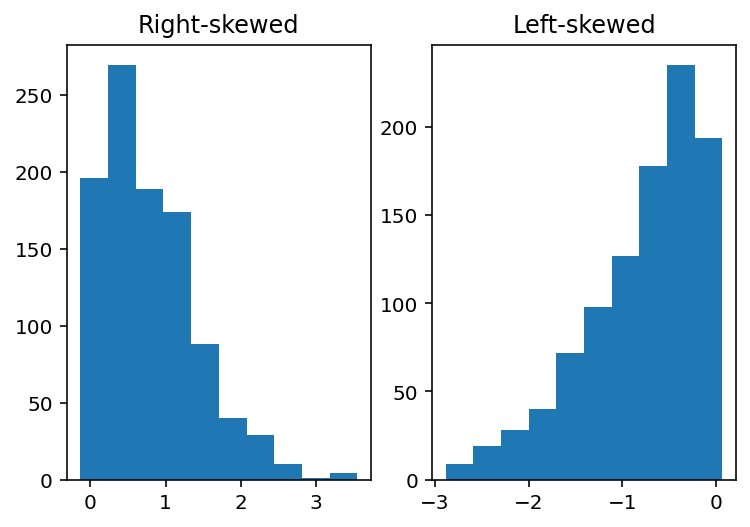

Skewed data¶

Skew means there are values elongating one of the “tails” of a distribution.

Positive/right skew: the tail is pointing to the right.

Negative/left skew: the tail is pointing to the left.

rskew = ss.skewnorm.rvs(20, size = 1000) # make right-skewed data

lskew = ss.skewnorm.rvs(-20, size = 1000) # make left-skewed data

fig, axes = plt.subplots(1, 2)

axes[0].hist(rskew)

axes[0].set_title("Right-skewed")

axes[1].hist(lskew)

axes[1].set_title("Left-skewed")

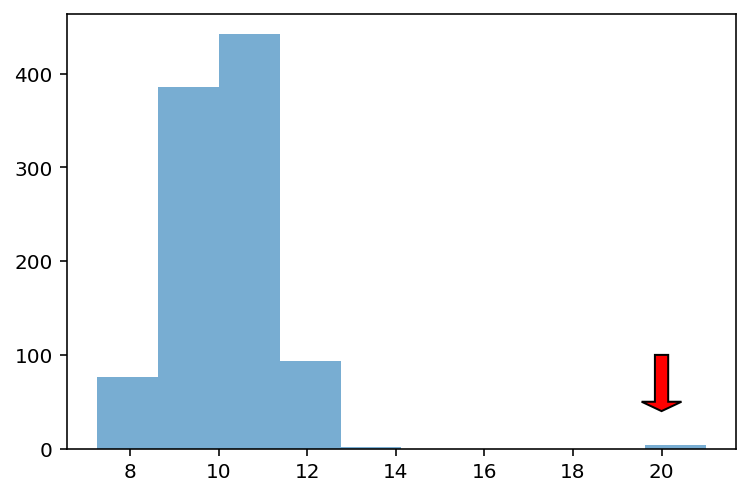

Outliers¶

Outliers are data points that differ significantly from other points in a distribution.

Unlike skewed data, outliers are generally discontinuous with the rest of the distribution.

Next week, we’ll talk about more ways to identify outliers; for now, we can rely on histograms.

norm = np.random.normal(loc = 10, scale = 1, size = 1000)

upper_outliers = np.array([21, 21, 21, 21]) ## some random outliers

data = np.concatenate((norm, upper_outliers))

p = plt.hist(data, alpha = .6)

plt.arrow(20, 100, dx = 0, dy = -50, width = .3, head_length = 10, facecolor = "red")

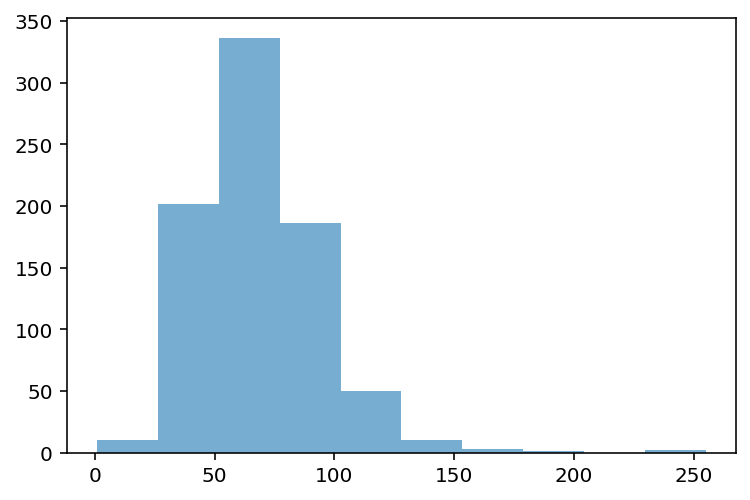

Check-in¶

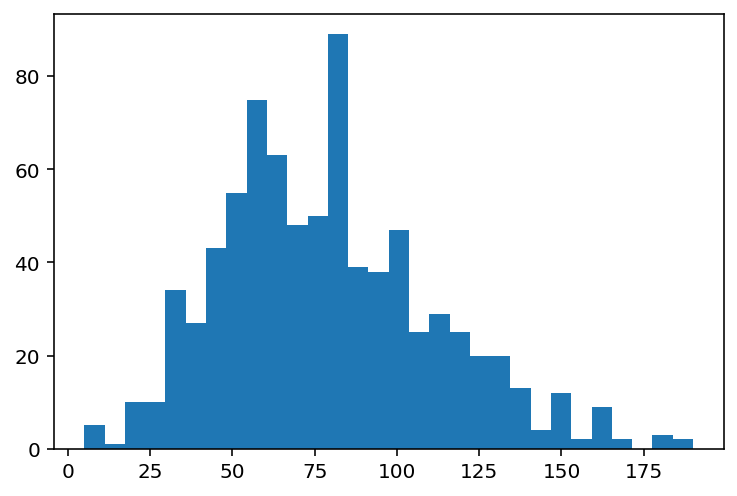

How would you describe the following distribution?

Normal vs. skewed?

With or without outliers?

p = plt.hist(df_pokemon['HP'], alpha = .6)

Check-in¶

How would you describe the following distribution?

Normal vs. skewed?

With or without outliers?

p = plt.hist(df_pokemon['Sp. Atk'], alpha = .6)

Check-in¶

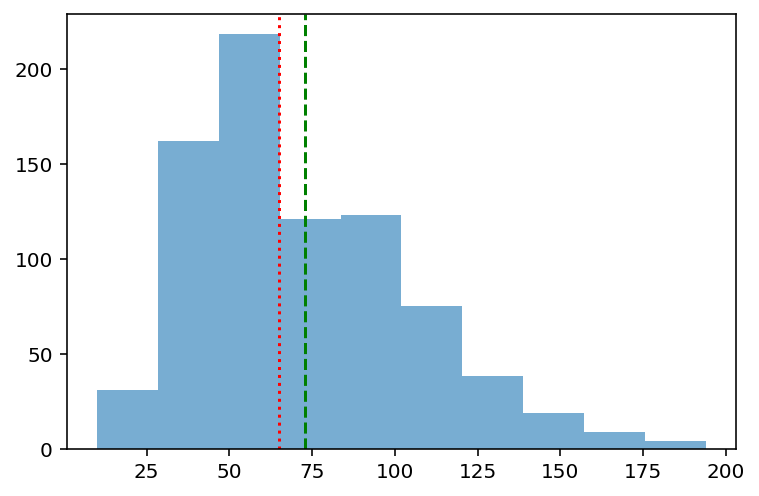

In a somewhat right-skewed distribution (like below), what’s larger––the mean or the median?

p = plt.hist(df_pokemon['Sp. Atk'], alpha = .6)

Solution¶

The mean is the most affected by skew, so it is pulled the furthest to the right in a right-skewed distribution.

p = plt.hist(df_pokemon['Sp. Atk'], alpha = .6)

plt.axvline(df_pokemon['Sp. Atk'].mean(), linestyle = "dashed", color = "green")

plt.axvline(df_pokemon['Sp. Atk'].median(), linestyle = "dotted", color = "red")

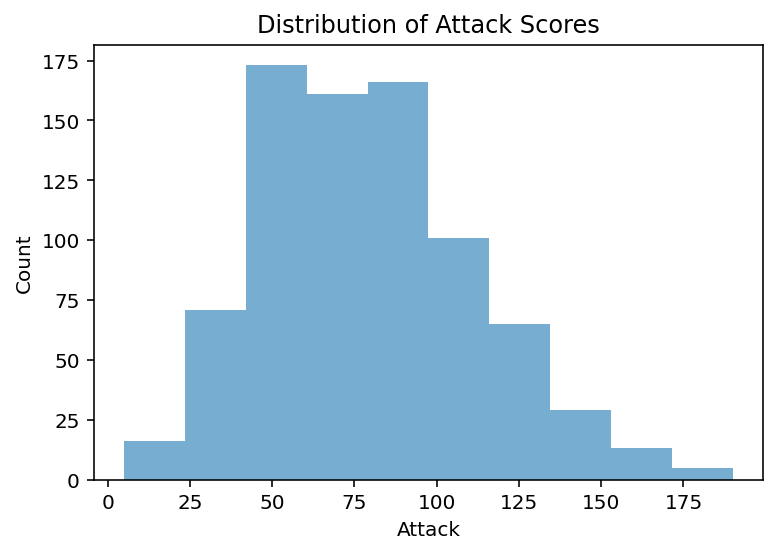

Modifying our plot¶

A good data visualization should also make it clear what’s being plotted.

Clearly labeled

xandyaxes, title.

Sometimes, we may also want to add overlays.

E.g., a dashed vertical line representing the

mean.

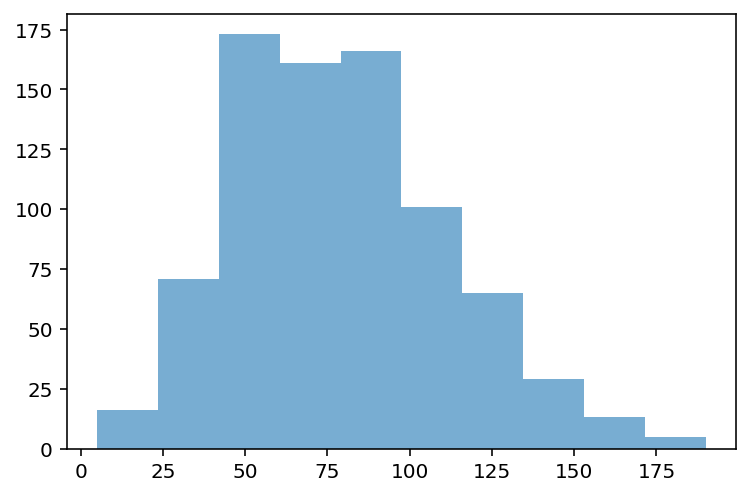

Adding axis labels¶

p = plt.hist(df_pokemon['Attack'], alpha = .6)

plt.xlabel("Attack")

plt.ylabel("Count")

plt.title("Distribution of Attack Scores")

Adding a vertical line¶

The plt.axvline function allows us to draw a vertical line at a particular position, e.g., the mean of the Attack column.

p = plt.hist(df_pokemon['Attack'], alpha = .6)

plt.xlabel("Attack")

plt.ylabel("Count")

plt.title("Distribution of Attack Scores")

plt.axvline(df_pokemon['Attack'].mean(), linestyle = "dotted")

Scatterplots¶

What are scatterplots?¶

A scatterplot is a visualization of how two different continuous distributions relate to each other.

Each individual point represents an observation.

Very useful for exploratory data analysis.

Are these variables positively or negatively correlated?

A scatterplot is a bivariate plot, i.e., it displays at least two variables.

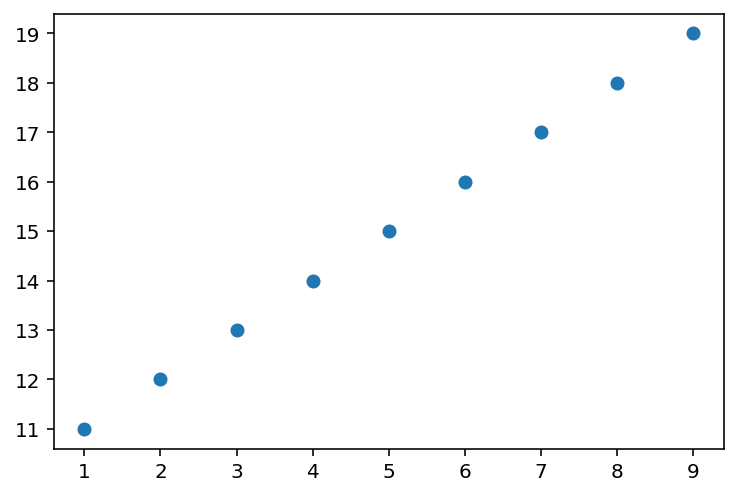

Scatterplots with matplotlib¶

We can create a scatterplot using plt.scatter(x, y), where x and y are the two variables we want to visualize.

x = np.arange(1, 10)

y = np.arange(11, 20)

p = plt.scatter(x, y)

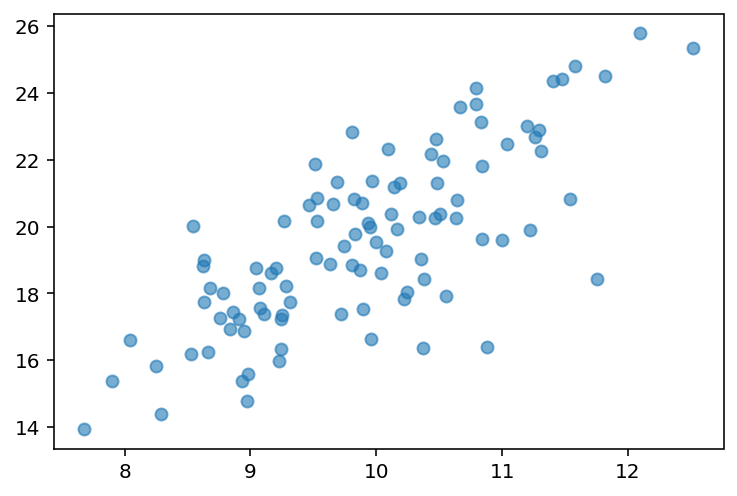

Check-in¶

Are these variables related? If so, how?

x = np.random.normal(loc = 10, scale = 1, size = 100)

y = x * 2 + np.random.normal(loc = 0, scale = 2, size = 100)

plt.scatter(x, y, alpha = .6)

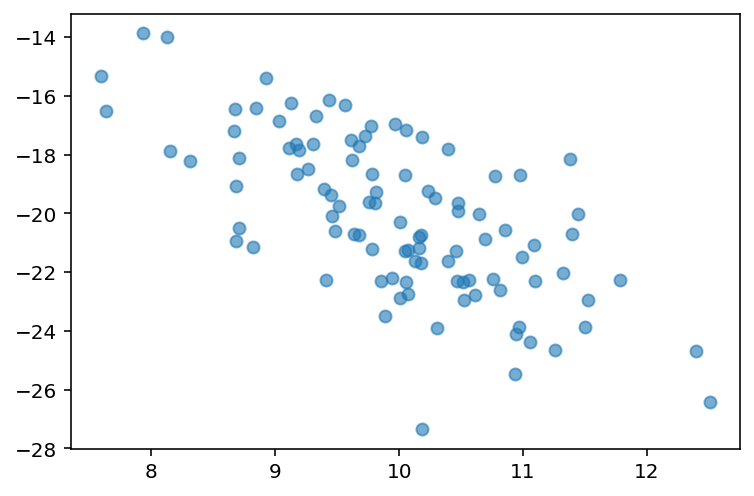

Check-in¶

Are these variables related? If so, how?

x = np.random.normal(loc = 10, scale = 1, size = 100)

y = -x * 2 + np.random.normal(loc = 0, scale = 2, size = 100)

plt.scatter(x, y, alpha = .6)

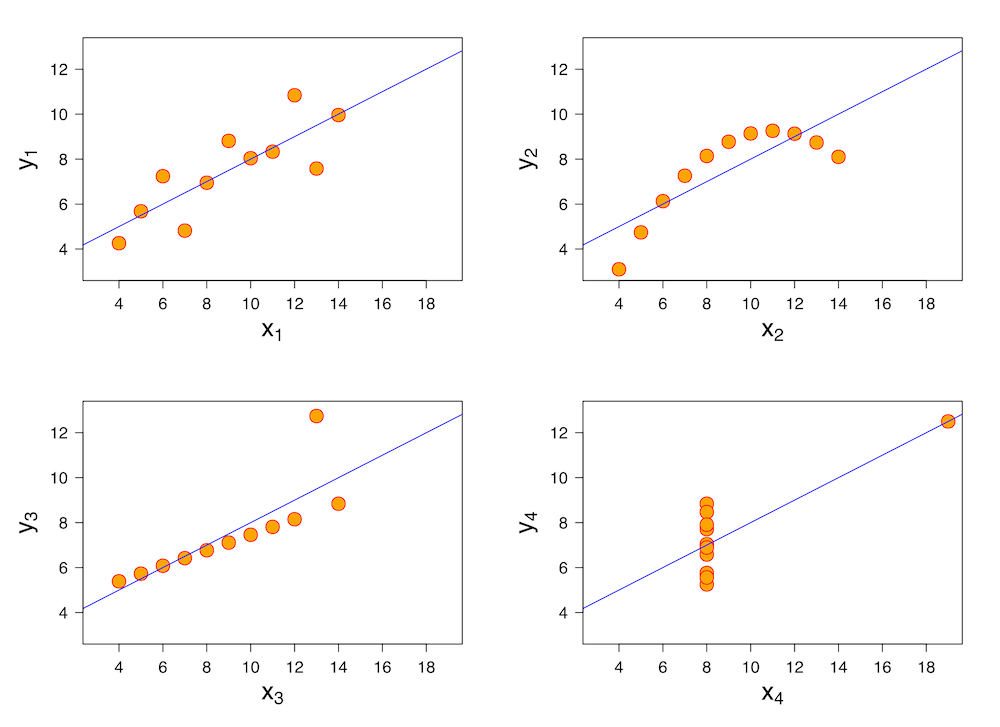

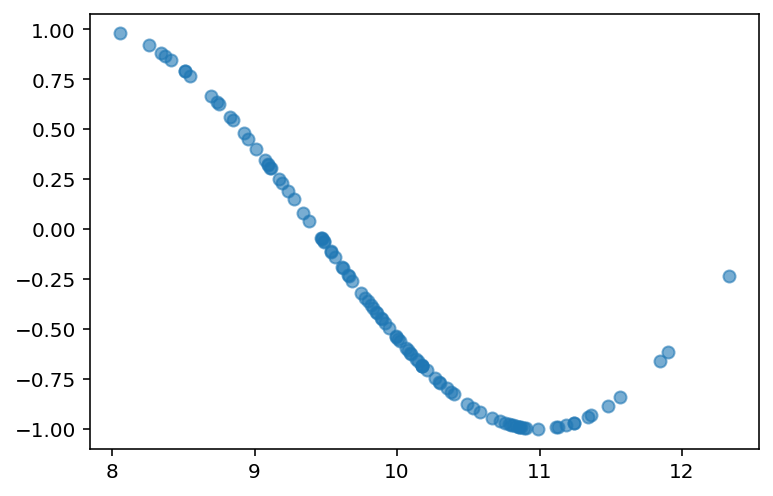

Scatterplots are useful for detecting non-linear relationships¶

x = np.random.normal(loc = 10, scale = 1, size = 100)

y = np.sin(x)

plt.scatter(x, y, alpha = .6)

Check-in¶

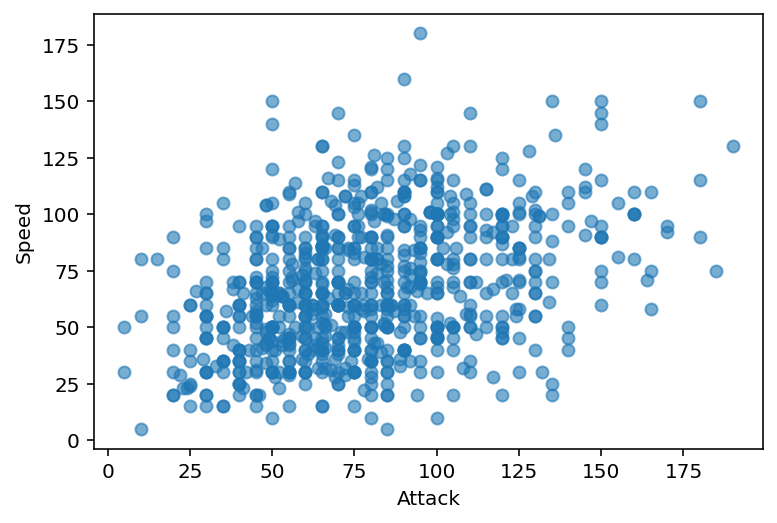

How would we visualize the relationship between Attack and Speed in our Pokemon dataset?

### Check-inSolution¶

Perhaps somewhat positively correlated, but not too much.

Side note: what would it mean for the Pokemon game if all these attributes (Speed, Defense, etc.) were extremely positively correlated?

plt.scatter(df_pokemon['Attack'], df_pokemon['Speed'], alpha = .6)

plt.xlabel("Attack")

plt.ylabel("Speed")

Scatter plots with pyplot express¶

Bubble plots¶

Scatter plots with resizable circular markers are often called bubble plots. Note that the color and size data is added to the hover information. You can add other columns to the hover data using the hover_data argument in px.scatter.

import plotly.express as px

df = px.data.iris()

fig = px.scatter(df, x="sepal_width", y="sepal_length", color="species",

size='petal_length', hover_data=['petal_width'])

fig.show()Color can be continuous, as below, or discrete/categorical, as above.

df = px.data.iris()

fig = px.scatter(df, x="sepal_width", y="sepal_length", color='petal_length')

fig.show()The symbol argument can also be mapped to a column. A wide range of symbols is available.

df = px.data.iris()

fig = px.scatter(df, x="sepal_width", y="sepal_length", color="species", symbol="species")

fig.show()Grouped Scatterplots¶

Scatterplots support grouping - so-called faceting.

df = px.data.tips()

fig = px.scatter(df, x="total_bill", y="tip", color="smoker", facet_col="sex", facet_row="time")

fig.show()Adding lines¶

The estimated linear function can be superimposed on the scatterplot:

df = px.data.tips()

fig = px.scatter(df, x="total_bill", y="tip", trendline="ols")

fig.show()Barplots¶

What is a barplot?¶

A barplot visualizes the relationship between one continuous variable and a categorical variable.

The height of each bar generally indicates the mean of the continuous variable.

Each bar represents a different level of the categorical variable.

A barplot is a bivariate plot, i.e., it displays at least two variables.

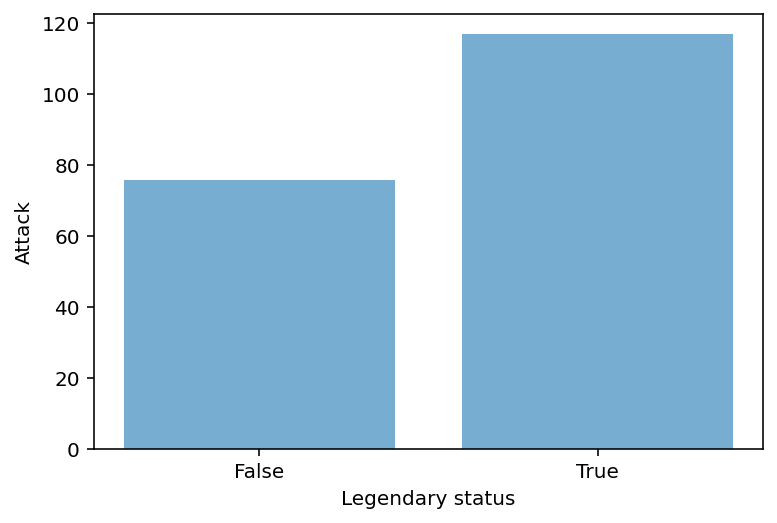

Barplots with matplotlib¶

plt.bar can be used to create a barplot of our data.

E.g., average

AttackbyLegendarystatus.However, we first need to use

groupbyto calculate the meanAttackper level.

Step 1: Using groupby¶

summary = df_pokemon[['Legendary', 'Attack']].groupby("Legendary").mean().reset_index()

summary### Turn Legendary into a str

summary['Legendary'] = summary['Legendary'].apply(lambda x: str(x))

summaryStep 2: Pass values into plt.bar¶

Check-in:

What do we learn from this plot?

What is this plot missing?

plt.bar(x = summary['Legendary'],

height = summary['Attack'],

alpha = .6)

plt.xlabel("Legendary status")

plt.ylabel("Attack")

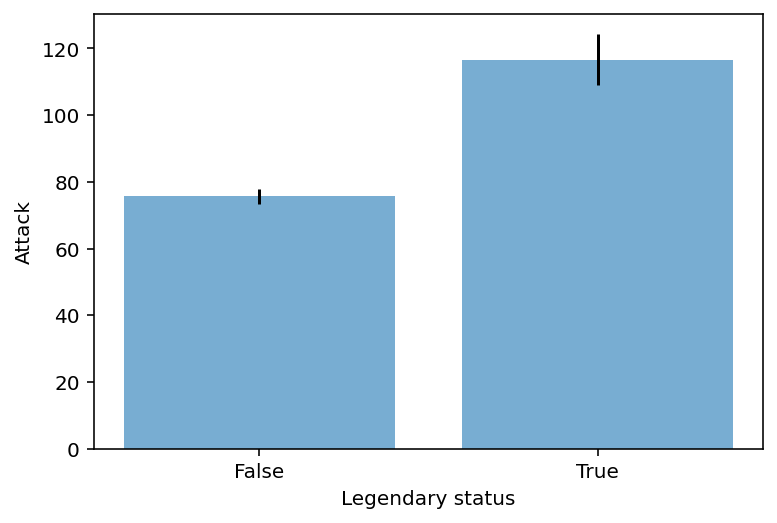

Adding error bars¶

Without some measure of variance, bar plots just tell us the

meanof each level.Ideally, we’d have a way to measure how much variance there is around that

mean.

Typically, error bars are calculated using the standard error of the mean.

Standard error of the mean¶

The standard error of the mean is the standard deviation of the distribution of sample means; in practice, it’s an estimate of how much variance there is around our estimate of the

mean.

Standard deviation, or , is a measure of how much scores deviate around the mean.

Standard error of the mean, or \sigma_\bar{x}, incorporates standard deviation, but also sample size, or .

\Large \sigma_\bar{x} = \frac{\sigma}{\sqrt{n}}

As increases, \sigma_\bar{x} decreases.

I.e., larger sample size decreases standard error of the mean––which is good for our estimates!

Turning standard error into error bars¶

An error bar represents a “confidence interval”.

Typically, the lower/upper bounds of a confidence interval are calculated by subtracting or adding 2 * \sigma_\bar{x} to the

mean.

Note: Next week, we’ll learn all about why this is!

Step 1: calculate standard errors with sem¶

sem_summ = df_pokemon[['Legendary', 'Attack']].groupby("Legendary").sem().reset_index()

sem_summ### Turn Legendary into a str

sem_summ['Legendary'] = sem_summ['Legendary'].apply(lambda x: str(x))

sem_summStep 2: Create plot using plt.errorbar¶

The

xandycoordinates are just from our original summaryDataFrame.The

yerris the standard error we just calculated.

plt.errorbar(x = summary['Legendary'], # original coordinate

y = summary['Attack'], # original coordinate

yerr = sem_summ['Attack'] * 2, # standard error

ls = 'none', ## toggle this to connect or not connect the lines

color = "black"

)

plt.xlabel("Legendary status")

plt.ylabel("Attack")

Step 3: Combining with plt.bar¶

plt.errorbar(x = summary['Legendary'], # original coordinate

y = summary['Attack'], # original coordinate

yerr = sem_summ['Attack'] * 2, # standard error

ls = 'none', ## toggle this to connect or not connect the lines

color = "black"

)

plt.bar(x = summary['Legendary'],

height = summary['Attack'],

alpha = .6)

plt.xlabel("Legendary status")

plt.ylabel("Attack")

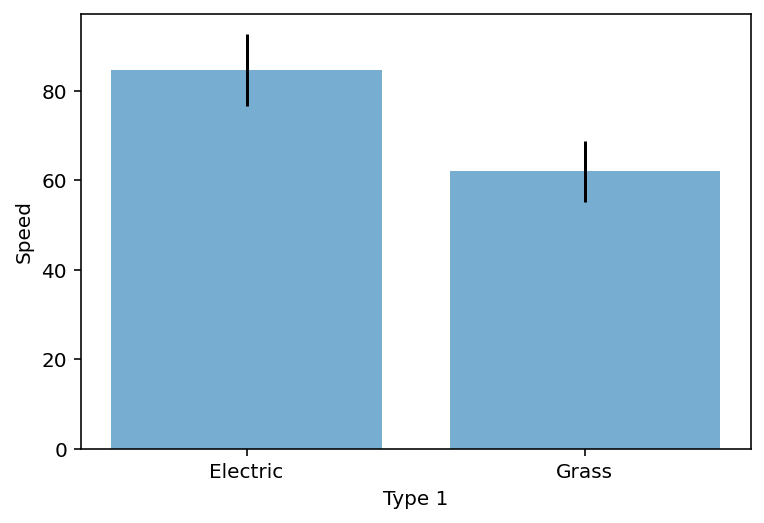

Check-in¶

Create a barplot with errorbars representing:

meanSpeedbyType 1Focusing only on Pokemone with a

Type 1ofGrassorElectric.

### Your code hereSolution¶

This is a multi-step one! Steps involved:

Filter our

DataFrameto be onlyGrassorElectric.Use

groupbyto calculate the meanSpeedbyType 1.Use

groupbyto calculate the standard error of the mean forSpeedbyType 1.Use

plt.barandplt.errorbarto plot these data.

Step 1¶

df_filtered = df_pokemon[df_pokemon['Type 1'].isin(['Grass', 'Electric'])]

df_filtered['Type 1'].value_counts()Grass 70

Electric 44

Name: Type 1, dtype: int64Steps 2-3¶

summary = df_filtered[['Type 1', 'Speed']].groupby("Type 1").mean().reset_index()

summarysem_speed = df_filtered[['Type 1', 'Speed']].groupby("Type 1").sem().reset_index()

sem_speedStep 4¶

plt.errorbar(x = summary['Type 1'], # original coordinate

y = summary['Speed'], # original coordinate

yerr = sem_speed['Speed'] * 2, # standard error

ls = 'none', color = "black"

)

plt.bar(x = summary['Type 1'],

height = summary['Speed'],

alpha = .6)

plt.xlabel("Type 1")

plt.ylabel("Speed")

Plotly express¶

Plotly Express is an easy-to-use, high-level interface to Plotly that works with a variety of data types and creates easy-to-style charts.

With px.bar, each row of a DataFrame is represented as a rectangular bar. To aggregate multiple data points into the same rectangular bar, see the histogram documentation.

In the example below, there is only one row of data per year, so one bar per year is displayed.

import plotly.express as px

data_canada = px.data.gapminder().query("country == 'Canada'")

fig = px.bar(data_canada, x='year', y='pop')

fig.show()Bar charts with long data¶

Long data has one row per observation and one column per variable. This is suitable for storing and displaying multidimensional data, i.e. with dimensions greater than 2. This format is sometimes called “ordered”.

To learn more about how to provide a specific form of column-oriented data to 2D-Cartesian Plotly Express functions such as px.bar, see the Plotly Express Wide-Form Support in Python documentation.

long_df = px.data.medals_long()

fig = px.bar(long_df, x="nation", y="count", color="medal", title="Data in long format")

fig.show()Let’s take a look at the data:

long_dfBar charts with wide data¶

Wide data has one row for the value of one of the first variables and one column for the value of the second variable.

This is suitable for storing and displaying two-dimensional data.

wide_df = px.data.medals_wide()

fig = px.bar(wide_df, x="nation", y=["gold", "silver", "bronze"], title="Data in wide format")

fig.show()Let’s see what the data looks like in wide format:

wide_dfColored Bars¶

The bar chart can be customized with keyword arguments, for example to use a continuous color as below, or a discrete color as above.

df = px.data.gapminder().query("country == 'Poland'")

fig = px.bar(df, x='year', y='pop',

hover_data=['lifeExp', 'gdpPercap'], color='lifeExp',

labels={'pop':'Population - Poland'}, height=400)

fig.show()df = px.data.gapminder().query("continent == 'Oceania'")

fig = px.bar(df, x='year', y='pop',

hover_data=['lifeExp', 'gdpPercap'], color='country',

labels={'pop':'population of Canada'}, height=400)

fig.show()Stack vs Grouped Bars¶

When multiple rows have the same x value (here Female or Male), the rectangles are stacked on top of each other by default.

df = px.data.tips()

fig = px.bar(df, x="sex", y="total_bill", color='time')

fig.show()The default behavior of a stacked bar chart can be changed to grouped (also known as clustered) using the barmode argument:

df = px.data.tips()

fig = px.bar(df, x="sex", y="total_bill",

color='smoker', barmode='group',

height=400)

fig.show()Grouping bar charts¶

Using the facet_row (or facet_col) keyword arguments will create grouped subplots where different rows (or columns) correspond to different values facet_row.

df = px.data.tips()

fig = px.bar(df, x="sex", y="total_bill", color="smoker", barmode="group",

facet_row="time", facet_col="day",

category_orders={"day": ["Thur", "Fri", "Sat", "Sun"],

"time": ["Lunch", "Dinner"]})

fig.show()Conclusion¶

This concludes our first introduction to data visualization:

Working with

matplotlib.pyplot.Creating basic plots: histograms, scatterplots, and barplots.

Next time, we’ll move onto discussing seaborn, another very useful package for data visualization.